$10,000 Prize Announced by Farmer, Sproat, and Witzel

in Conjunction with the Publication of

The Collapse of the Indus-Script Thesis: The Myth of a Literate Harappan Civilization (PDF)

(Text of the Prize Offering fixed in December 2004; Webpage formatting updated February 2007)

Prize Announcement

Turn up just one Indus inscription that contains at least 50 symbols distributed in the outwardly random-appearing ways typical of true scripts contemporary to the Indus system, and we will (1) declare our model to be falsified and (2) will write a check to the discoverer or discoverers for $10,000.

Ground rules: Due to the many forgeries associated with the 130-year-old Indus-script thesis (see, e.g., Witzel and Farmer 2000; Farmer 2003), before becoming a candidate for the prize the inscription (1) must be clearly provenanced from a known Indus archaeological site and (2) must be accepted as genuine by a consensus of recognized Indus researchers.

The offer, backed by an anonymous donor, is good throughout Farmer’s lifetime.

See further “A Note on Falsification” (p. 48 in our paper, reproduced at the end of this page).

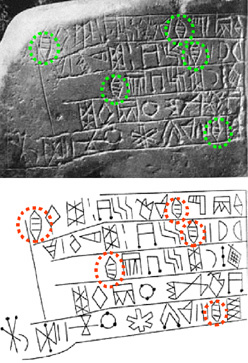

For an example of what we mean by ‘random-appearing’ sign duplications, see the Linear Elamite inscription (which contains roughly 50 signs) compared below with the longest known Indus inscription (which contains 17 non-repeating signs). Similar examples can be provided from other contemporary scripts:

Like inscriptions in all true scripts from the late 3rd millennium BCE, this Linear Elamite inscription contains a great deal of random-appearing sign repetition, which in this case is an apparent ‘marker’ of high levels of sound coding:

– 1 sign repeats 5 times (circled)

– 2 signs repeat 4 times

– 8 signs repeat 2-3 times each

Over 30 sign repetitions in the inscription

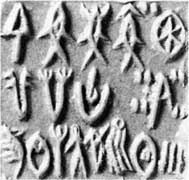

The longest Indus inscription on one surface (M-314a) is typical of Indus inscriptions in consisting predominantly of non-repeating high-frequency signs (measured in the corpus as a whole). (Note that no sign repetitions at all occur in this particular inscription, although at least 10 of the highest frequency Indus signs show up in it.) The contrast with Linear Elamite is extreme.

For a full discussion of anomalous sign frequencies in the Indus corpus, see Farmer, Sproat, and Witzel (2004: 26-38).

Actual size of the longest known Indus inscription: a tiny .9 x 1 inches (2.41 x 2.54 cm)!

Extract from p. 48 of Farmer, Sproat, and Witzel (2004):

The Collapse of the Indus-Script Thesis: The Myth of a Literate Harappan Civilization ((PDF)

A Note on Falsifiability

It will probably surprise many readers to discover that the standard view that the Indus civilization was literate has been an assumption and not a conclusion of previous studies. While debate over the language of Indus inscriptions has had a long and acrimonious history, not one of the thousands of articles or books written on the topic since the 1870s included any systematic justification for the belief that the inscriptions were in fact linguistic.

The claim that historical fields follow methods different from those of other sciences is still frequently repeated. Given the political abuses to which history is subject, we consider this to be a dangerous claim, and believe that the same rigor must be demanded in history as in any other scientific field. With this in mind, in closing we would like to acknowledge the heuristic nature of our work and briefly consider some conceivable conditions under which it might be overturned.

Specifically, we would consider that our model of Indus symbols was falsified, or at least subject to serious modification, if any of the following conditions were fulfilled:

1. If remnants were discovered of an Indus inscription on any medium, even if imperfectly preserved, that contained clear evidence that the original contained several hundred signs;

2. If any Indus inscription carrying at least 50 symbols were found that contained unambiguous evidence of the random-looking types of sign duplications typical of ancient scripts;

3. If any bilingual inscription were discovered that carried a minimum of 30 or so Indus symbols juxtaposed with a comparable number of signs in a previously deciphered script;

4. If a clear set of rules were published that allowed any researcher, besides the original proposer of those rules, to decipher a significantly large body of Indus inscriptions using phonetic, syntactic, and semantic principles of no greater number or complexity than those needed to interpret already deciphered scripts;

5. If a ‘lexical list’ were discovered that arranged a significantly large number of Indus signs in ways similar to those found in Near Eastern school texts.

Due to the long record of doctored evidence and forgery that is part of the Indus-script story (cf., e.g., Witzel and Farmer 2000, Farmer 2003), any discoveries of this type would have to be accepted by a broad consensus of Indus researchers before we would consider our model to be falsified or subject to major modification. We would like to conclude that while we consider it highly improbable that any of these five discoveries will ever be made, we would welcome them if they were, since when considered alongside the many anomalies in the Indus symbol system, any of those discoveries would necessarily trigger a radical rethinking of current views of early writing systems.

©2004, 2007 Steve Farmer, Richard Sproat, and Michael Witzel

Feb 2023 format changes from web server migration.